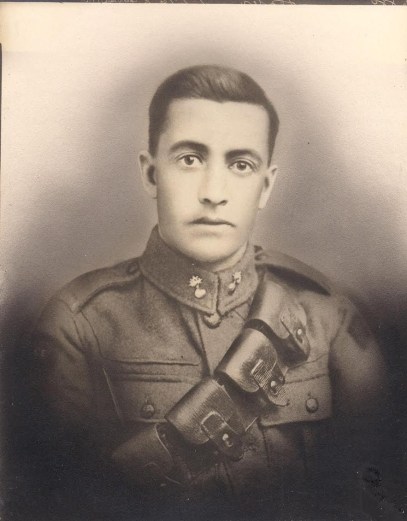

Joseph James Foster, 1916.

By January of 1919, Joseph had been away from his family for two and a half years and had been in France and Belgium for some very brutal parts of the war. There was no record of him ever having been injured or sick, not even the very common ailment of scabies.

In the months after armistice, the armies found themselves with a tremendous amount of personnel, equipment, and animals scattered throughout Northern France and Belgium that needed to be reorganized and reassigned, and in several cases there was also a great deal of infrastructure that needed to be repaired in order to facilitate that level of movement of people and machinery.

In the case of troops from overseas, there was also a tremendous backlog in terms of determining how and when to get men home. This resulted in battalions with a lot of time on their hands, attending dances, organizing sports activities, parading, and then performing light duties as needed.

The entry for the 12th Engineers on January 27, 1919 in the war diary is almost identical to the days that preceded it and the days that followed it. They had been in Belgium since armistice, and there was no sign of them moving significantly anytime soon. The Battalion built a boxing ring that day… this is the only thing of note. But for my great-grandfather, that day was the start of a dramatic few months that would precede his returning to his family in Toronto.

He went missing from his billet that evening, and would not return until January 31st, nearly four full days (3 days and 22 and a half hours to be precise), at which point he was arrested by the Regimental Sergeant Major for being absent without leave, and, more seriously, for stealing a horse belonging to the government and selling it.

The stable master had discovered a horse missing on the night of January 27th, and quickly organized a search party to look for the animal. They found the horse in question that same night, and woke the man on whose property the horse was found to piece together what had happened. According to the statement provided by one of the men who had been part of the search for the horse and who was present when the civilian who had bought it was describing the events, the civilian stated that he had been sold the horse by two Canadian soldiers:

He described one was being French-Canadian and the other as a short, dark man who he thought was a cook.

This short, dark man matched the description of Joseph James Foster. Although there is no direct mention of cook’s training in his service file, there are several mentions of men being sent for cook’s training after the 124th disbanded and was dispersed. Unfortunately the parts of the court martial file with Joseph’s verbatim statements are too faded to read, but the word “cook” is legible on one page.

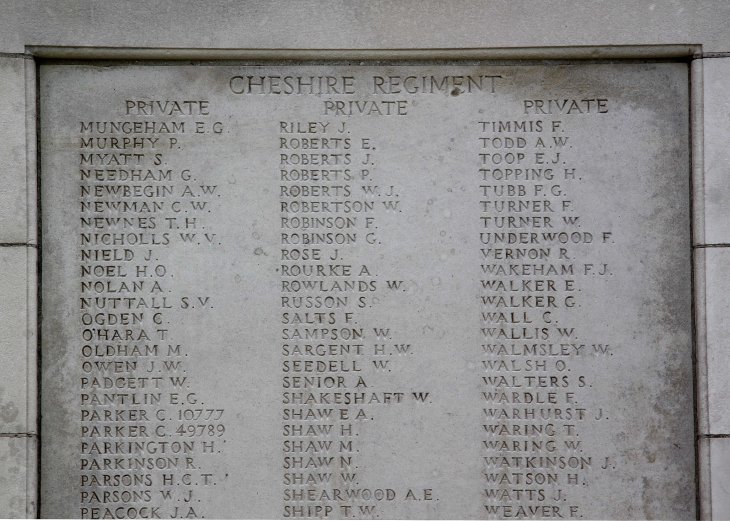

He was held in confinement for 29 days before his trial on February 28, 1919. He and another soldier, Dvr. A. Jobin, a French-Canadian soldier, were accused of stealing a horse from the stables of the battalion on the evening of January 27th, and then selling it for 700 francs to a nearby civilian. Both men pleaded guilty to being absent without leave, but not guilty to the charge of stealing the horse. Evidence against him included the statements of all the men who had assisted in finding the horse, as well as his previous punishment from October of 1917 when he had been found drunk on active duty, and had been given 14 days worth of “field punishment No.1.” This punishment, nicknamed “crucifixion” by many soldiers, entailed labour duties and attachment to a fixed object such as a post or wheel for two hours a day. According to the Canadian War Museum’s page on discipline and punishment, this was considered a particularly humiliating and degrading practice.

Despite their plea, both men were found guilty on both counts and were sentenced to four months in military prison. The convictions and sentences from the field court martial were upheld on review by a judge, and Joseph was sent to military prison in March of 1919. It appears that he served his full four months sentence, as it wasn’t until July of 1919 that he finally boarded a ship for his return to Canada, landing in Halifax on July 23, 1919, just a few days under three years from when he sailed for Britain. Three days later, he was back in Toronto, where he was officially discharged from the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Joseph went to work as a postal clerk, and by early 1920, he and his wife Mary Alice, were expecting their third child. This baby, a boy, was born in November of 1920, and he was named Joseph James after his father. This baby was also my Grandfather. Six years later, another baby, a daughter, was born. Joseph was 41 at this time.

By late 1937, 51-year old Joseph was in sales with a dairy. At least one of his sons was also working as a dairyman. His two older sons were 26 and 23 respectively. The eldest was married with a son of his own, and the younger was engaged. Joseph’s two younger children were 17 and 10 respectively. On November 10, 1937, Joseph took some sheets and tied them to a bannister, then around his own neck. He was 51 years old.

Family lore says that it was my Grandfather, Joseph James Jr., who found him. His record of death states that he died of strangulation by way of suicide. My Grandfather’s oldest brother was on record as the informing party.

Soldier suicide after the great war has not been widely studied, but it has been fairly universally acknowledged that this war had a profound effect on the mental health of many of the people who participated. This is a phenomenon that we recognize much more broadly today, and supports and treatment are available. I have no way of knowing what specific series of events or state of emotional health contributed to my Great-Grandfather’s death in 1937. All I know is that he passed away in a very sad manner, and that it is very possible that he had been deeply impacted by what he experienced between 1916 and 1919.

My great grandmother, Mary Alice Pickering, married again in 1938 to widower Elias Williams. The following year, the world was engulfed in war again, and the pattern I have been tracing for the past year began to repeat itself. My Grandfather, Joseph James Foster Jr. enlisted in 1941, soon after marrying my Grandmother, Florence Elizabeth Miller. My Grandmother’s father, John Russell Miller, had also been in the Great War. Her brother, Samuel, was already overseas in the RAF when she married my Grandfather. In 1942, Samuel was shot down and killed. My Grandfather, however, did make it through the war, and returned in 1946 ready to resume his life as a salesman with CIL paints, and begin his family life with my Grandmother in earnest.

Tomorrow, I look forward to being able to share this story and the stories of the 51 other men in this series at the Armistice 100 events here in Edmonton, Alberta. It has been an honour to share these stories over this past year. I am looking forward to the next evolution of this project, which I will share more about in the weeks and months to come.